Here are some reviews of books by Carol Lynn Stevenson Grellas

Chronicling her father's battle with failing health and dementia, the author’s book contains two dozen poems that examine the physical and emotional side of the condition. While Grellas' father is the one directly impacted by his health, the case of dementia is one that spreads to the entire family. Capturing the emotional turmoil and battle of wills entailed in being the caregiver for one’s own parent, each of these poems offers rays of hope and commiseration for the harder struggles. These poems are not meant to inspire pity or condolences but rather illuminate the feelings and internal dialogue of a person doing everything they can to will a parent back to good health and better days.

Depending on one’s circumstances, these poems will either be eye-opening or aim straight for the heartstrings and memories. Written with a vocabulary that captures every heart swell and crushed hope, the selections are short but make a deep, lasting impact. The poet’s choice of words is light to the point of being ghostly, but underneath feathery metaphors lies the ultimate weight of inevitable mortality. Each poem lies in a sequence that tells a story of good days and eventual decline, ending on the necessity to move on while always remembering. Because of the in-the-moment perspective in these poems, this book may be difficult for someone going through a similar scenario as the author had but should still provide light and catharsis once the struggle of caregiving has ended. Nearly pocket-sized and well able to be read in just an hour or so, this short collection of poems is no less emotional for its brevity.

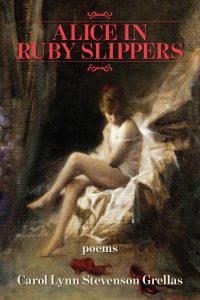

I’m a fan of poetic forms. Haiku. Sonnet. Pantoum. The elusive sestina. I think there is something magical that happens when a poet jumps into a scaffolding. The scaffolding lifts us, readers and author, to unique connections and dramatic conclusions. Which makes Alice in Ruby Slippers, a collection of poems by Carol Lynn Stevenson Grellas, an unexpected adventure. The mixing of tales in its titles signifies we’re going on a journey of what we think – on entirely new and independent paths, devised by Grellas, just as she’s modifying the poetic forms to suit her voice and her plan for her poems. Lured by the promise of familiar sonnets and other poems, I’m granted entry into a world of Grellas’ imagination.

What are the elements that make this journey wild and wonderful? Let’s talk about rhyming. Rhyme is a traditional component of many poetic forms. What makes rhyme special, I think, is the expected connections and clever use of language as well as the emphasis on the sound of your poem. In her poem, “Without Vision,” she writes: “a secret illness writes itself in Braille / soundless as the unseen breath of trees, / it lives, grows, sighs and breathes within / the shadow of the body’s fleshy veil” (73). These lines are jammed with exciting rhyme. The end-rhymes, the middle of the line rhymes. My favorite is the hardworking rhyme of trees/breathes which replicates the soft sighs immediately preceding it. The rhyme that works like this embeds the reader in the experience of the poem.

Grellas makes sound a foundation of her poems. In “On Underestimating the Aftermath,” Grellas writes about a daughter caring for dying parents. Despite the daughter’s hard work and knowledgeable caretaking, the grief and loss are profound. “But when dying was over, their eulogy read … / there was no one to tell me, good girl. They were dead,” (71). In the repetition of single syllables and the final simple three words, Grellas draw out the experience of a huge loss and finality of that singular loss. In “Since You’ve been Gone,” sound is the central component of the poem itself. Whether it's music that reminds the narrator of the passed person or how they “play / old messages to hear your voice again –“ (19) Grellas reminds us the sound evokes emotions and deftly wields sound to guide us through her poetic constructions.

Grellas also uses sound and rhyme and rhythm to reveal the speechless, soundless, almost sacred moments in life. In “The Cancer Diagnosis” a couple waits for information and Grellas documents the time “when nothing said conveys all thoughts repressed,” (24). Or in “The Sequoia,” Grellas writes about a moment of transcendence in the landscape, “through bars of golden beams across the sod, / she disappeared forever on the day / communion with a tree brought her to God” (46). The rhyme of sod and God spans the same space of the sacred communion that can make one disappears. Grellas’ words hold the space that sound cannot truly describe.

In the end Grellas challenges us to do what she does throughout Alice in Ruby Slippers – to do “Six Impossible Things after Reading Alice.” The last of which is a question that Grellas has tried to answer and hands to the reader for their thoughts. “I’d like to know why lives collide – name Love our home, none left denied” (80). After traveling through Grellas structured poems and remade foundations, I’m certainly willing to try – will you be too? I strongly recommend reading this rich book aloud so you too can reveal the sounds – and silences – evoked in Grellas beautiful lines.

The 102 poems in Carol Lynn Stevenson Grellas’ Epitaph for the Beloved (Finishing Line Press, 2019) are divided into seven sections, each introduced by a line in the nursery rhyme “Monday’s Child” though the lyrics have been changed from present tense (“Monday’s child is fair of face”) to past tense (“Monday’s Child Was Fair of Face”) and thus we have a history, a looking back on a life, rather than a contemporaneous description of or a prediction of one. One other change is the wording of the last day of the week. “And the child that is born on the Sabbath day / Is bonny and blithe, and good and gay” becomes “But the Child That Was Born on the Sabbath Day, Was Fair and Wise and Good and Gay.” The change seems to be for clarity, though “blithe” and “wise” are nowhere near synonyms and I’m not sure what that comma after “Day” adds to the reader’s comprehension.

The reason I comment on this structure is that in any odd-numbered list there is a middle term as in the fifteen stories in Joyce’s Dubliners. The eighth story in that collection (“A Little Cloud”) is central to the meaning of that book. In this book, the fourth section (Thursday’s Child) is the center, the fulcrum from which all the other poems ascend or descend. The fourth section deals with the dissolution of the speaker’s marriage. Leading up to that section we have poems of childhood, motherhood, and grief, and following that section, we have poems of remarriage, nostalgia, and resolve.

But the poems in this middle section are the most passionate and the strongest in the book with titles like “Womanizer,” “Conman-Duplicitous,” “Sleeping Beauty, Betrayed,” “Detonate” and “The Vibrator,” a poem about the gift that a husband gave a wife with the refrain “you gave me a vibrator.” Here is the savage last stanza:

And here, I would say to you now, is the box

that sits bare and unfilled, which needs

no replacements. Here is the case which you

happened to leave while taking the vibrator

upon our divorce which I never questioned

knowing you’d need it—

far more than I.

The long dash above that separates the last line (“far more than I”) from the rest of the stanza is a typical strategy for many poems in this volume in which the last line is often set off from the rest of the poem, privileging it, investing it with dramatic and significant isolation.

Here are some examples:

Some of Grellas’ word choices are surprising and arresting as when she writes in “Mouse Queen” “you are an enigma of narrowing bones” or in these lines from “Caterpillar Prayers”:

You were a butterfly

in the meadowwhere no viewer

could see your gracesave the birdlike seraph

perched on a nearbymagnolia leaf

At other times, an occasional cliché (“pearly whites”) or a solecism (“laying on a bed”) appears, and every once in a while the language becomes a little precious, a little strained, as in “the air blued and bruised / from lies” [“Conman-Duplicitous”] or “how no / amount of plea undoes the fate / of any willful heart.” [“Breached”]

Still, so much of the diction in these poems is winning.

Dog, I am sorry

that you have gone hungry.

I have been a glutinous[1] fool. [“Wild Thing”]

This is the kind of poem,[2] that will sleep with you

when no one’s looking. [“Bad Poem”]

And so much of the sentiment in these poems is not to be resisted as when Grellas writes of her children, “They are the poems I’ve yet / to write as they will become a part of me / no matter what devastation the world / sends my way” [“If I Should Die before I Wake[3] Remember…”] and also when she writes memorably of herself, “A prelude to ecstasy is all that I ask.” [“Meet Me in the Countryside”]

As a “prelude to ecstasy,” read these poems of face, grace, woe, distance, loving, living, and wisdom, poems where “the moonlight knows your name.”

Alice in Ruby Slippers. Carol Lynn Stevenson Grellas. Kelsay Books.

Alice in Ruby Slippers by Carol Lynn Stevenson Grellas uses the rather unusual title to give us a clue to the book's theme. The title references two modern female pop-culture icons: Alice Liddell from Alice in Wonderland and Dorothy Gale from The Wizard of Oz. Through this, the reader is told that the book will be about women; that the voice in the book will be—like Dorothy and Alice—young, virginal, and on a quest (Dorothy wanted to get back home; Alice simply to understand the bewildering world in which she suddenly finds herself). The book frequently returns to these two ideas. Before the main text begins, the reader finds quotations by Lewis Carroll and Frank L. Baum. Carroll speaks of believing unbelievable things; the author quotes the famous line from the film version of Baum's The Wizard of Oz, "A heart is not judged by how much you love; but by how much you are loved by others." And the book's dedication is "for my mother."

All of these elements signal what we will find in that poems that follow. The opening poem, "Lost in Kansas," refers, of course, to Dorothy's situation before the tornado transports her to Oz and states the narrator's desire to settle, to find repose, to be secure. This desire is expressed in a poetic epistle to the Good Witch Glinda. The poem ends with the lines, "I've clicked my heels not once but thrice, / And still can't find a place called home,/ and still can't find a place called home." The first poem is an expression of a desire, a wish, that runs all through the book.

The first cluster of poems relates to the death of a mother. The very poignant poems, "Since You've Been Gone," has the sorrowful, powerful line, "A dream can be a devastating place / though more alarming still to wake and face / the truth of what is real." The first section of the book deals with loss. But loss never simply involves the person who is lost and the one who lost that person. Many poems represent memories of growing up, but also the terrible liturgy of cancer treatment and the aftermath losing a mother. The section also contains meditations on bereavement, poems that parallel literary reference with the narrator's loss, mythic reference (Calypso, Titania, Rapunzel) and mention of other figures from scenarios of loss in well-known books and poems.

Pop culture is better known that literature or classical mythology, and the book draws on these sources as well. Alice in Ruby Slippers mentions the film version of The Wizard of Oz several times, to Billie Holiday's grim song, "Strange Fruit." The poem, "Final Girl," about the stock character-girl who manages to survive the designs of a serial killer in modern films like Friday the Thirteenth, Halloween, and Nightmare on Elm Street. The last part of that sonnet is particularly poignant:

… Each scene unfurls

to horrors played, where killers never leave

an out for teenage boys, but final girls

are always spared. The females take reprieve—

beyond The Ring, What Lies Beneath is grim

but rest assured the final girl will win.

The poem is about female resilience. It is a marvelous way of stating, with grim irony, that women survive; like the iconic "final girl" in horror movies, they do not let themselves be overwhelmed and destroyed. The poem is a brilliantly reframed exploration of the nature of personal loss, drawing its images from a source not often used in writing about poignant and personal loss but marvelously powerful and effective.

The second section focuses on loss and incorporates the mythic. It is still focused upon iconic female figures. There are poems that reference Emily Dickenson, Alice Liddell, and others; there are more poems on family loss; and also exploration of female types in such poems as "Charlatan" and "She Walks in Cruelty" (an inversion of Byron's "She Walks in Beauty"); humorous poems such as "What's Under Your Kilt?", historical lyrics ("For Larnell Bruce, Jr.," "Odalisque"), poems that touch on issues ("A Mother's Message to her Son"), and poems that are intertextual, referencing well-known works by other authors (e.g., "As If the Hours Wait," subtitled, after reading, Because I could not stop for death (famous poem by Emily Dickenson).

Alice in Ruby Slippers encompasses a great deal of variety and contains a range of subjects; but always, the theme of womanhood and, especially, of loss, ties these varied poems together into a powerful unity. It explores the deep wells of personal loss, from the loss of childhood, of friendships, of place, but especially the profound grief of a daughter losing her mother. The poems are formalist, and this adds to their music and lyricism—and to the poignant sadness—the reader encounters in the book. When it comes to sadness, poetry can be cathartic—and such is the case with Alice in Ruby Slippers.

“I’ve long been haunted by the dualities of Carol Lynn Stevenson Grellas’ poetry: life and death, forgetting and the preservation of memory, resisting death while recognizing its beauty… Implied by the title, these poems are divided into the “shared” and the “sacred,” two large and meaningful parts to the collection. The “shared” poems are written mostly in sonnet form, as if Grellas’ poems are also sharing a form with late traditional poets, and they focus on family stories and heirlooms, implying the shared aspects of family, meaningful relationships and friendships, and of course, art. The second section, the “sacred,” focuses more on personal stories and the more personal takeaways from shared experiences, like how one perceives the family dynamic compared to another. This duality of the public and private proves to be haunting, especially in the poems that celebrate secrecy and memories never shared (until with us, the readers).

“What I’ve discovered after reading A Shared and Sacred Space is how each poem carries with it its own unique duality: its personal and collective power. I read some of these poems on an individual basis and loved them as they stood on their own, but now that I’ve read them as a part of a larger collection, I now better appreciate the larger resonance of these poems and the echoes they form across the collection. From love, motherhood, family heirlooms, and traditions, to religion, ailments, and the forever haunting loss of our furry loved ones, this “labyrinth of humanness unveiled” is a stunning collection of personal, shared, and confessional poetry that we surely all can relate to, and celebrate.

“Grellas lets us take a glimpse into the most treasured and personal aspects of her life, and like an ofrenda, a photo album, a guest list—by the end of the collection, all of us readers are those who have signed the guest book, leaving behind our own small contributions to poetry’s collective memory and taking something of Carol Lynn Stevenson Grellas’ with us.”

—McKenzie Lynn Tozan, Lit Shark Magazine

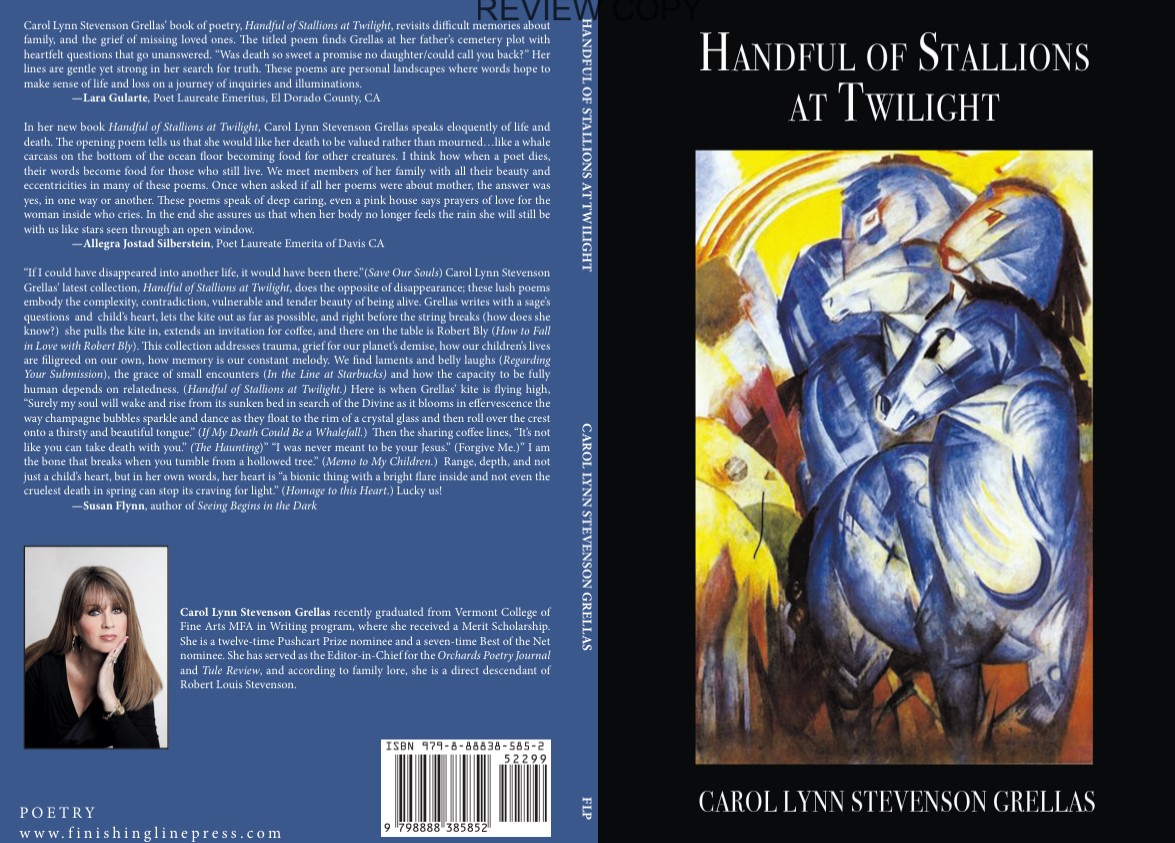

Every time I step into the work of Carol Lynn Stevenson Grellas, I feel like it is a blessing, though I know the poet, the narrator, and the poems inside are too humble to admit as much. Rather than point to her own deftness, her own ferocity in the face of the craft, Stevenson Grellas will invite you in for a cup of coffee or tea, biscuits, teach you how to fall in love with Robert Bly, and reminisce about a life lived. She’ll be that friend, too, who will ask about your day, and mean it, and she won’t shy away from the harder subjects of loss, prolonged grief, and even illness and suicide. These poems are gentle and kind but never shy, and while it’s figurative, the coffee is strong enough to carry us through, always hot, still steaming in our hands.

Stevenson Grellas is a frequent, welcome visitor to the subjects of memory, family, and loss, but these tough topics never go stale, predictable, or complacent when in her hands. Rather, her latest collection, Handful of Stallions at Twilight, leans unapologetically into the fragility of life and its suddenness. Just two pages into the collection, “Before Tomorrow Came” (2) offers the metaphor of being thrown a curveball, and I think this collection largely hinges on that premise: the concept of being thrown a curveball, navigating sudden change, missing what once was, and never even knowing when that curveball might come. Many poems here gesture to the suddenness of loss, like the narrator and her mother planning for a wedding in “August Bride,” everything beautifully and perfectly arranged, “and then she died” (83), leaving the narrator in a whirlwind, trying to reconcile after-wedding bliss with gut-wrenching, soul-skewing grief. Many poems, too, follow the trail of grieving something or someone who was lost too soon, too suddenly, too sadly—a beloved pet, a child, a literary editor, a father, and of course, a mother.

In “The Haunting” the narrator confesses: “Someone once asked if all my poems were about my mother. / Yes, I said as if there was a way to write without her / showing up, as guilt, as love, as tenderness” (56), and I believe this is the second of three hinges in the door of this work: the poet’s call to her mother, the perception of her mother through memory, and even Mother Earth. The mother is painted imperfectly, as every mother understandably should be, with her mistakes, her stubbornness, her nuances, but the collection resoundingly follows a narrator seeking her mother through the echoes in her life in which her mother still resides: a facial expression or turn of a hand that resembles her, an object that was once hers, a reflection that could just as easily be her as it is the narrator. And heart-wrenchingly, the direct foil for the search of mother is the finding of father, the sneaking reminders throughout these poems of a young narrator’s discovery and the lingering imprint of what that discovery was, what it meant for the family, how it was left unspoken, a “family secret / we were too ashamed to share” (44). Like the fond memories of the narrator’s mother, there are endearing ones for a father who could not cope, particularly the saving of innocent animals and gently carrying them back home in “Abandoned” (81-82) in a way he could not be.

Because, despite the dark corners of these poems, Stevenson Grellas never forgets to highlight the fragile beauty and the little glimmers of hope, found in and around the lost things. Life still has beauty and wonder despite grief—perhaps even more so because of it. Refreshingly, these glimmers can be found in the smallest of things: a sweater, a joke, a dress, a stunning bird, and flowers (so many flowers). I found myself frequently thinking back to Vanessa Diffenbaugh’s The Language of Flowers while reading this collection, due to Stevenson Grellas’ impressive vernacular and gesturing to such a range of species, and it made me think of the variety of messages these flowers carried—the chrysanthemums, petunias, and more—not to mention the memories tied to them through the gifting and planting of them.

There’s a gentle reminder, too (the third hinge in the door), of the importance of giving back to each other and to our planet: giving back to the bees, the birds, our loved ones, Mother Earth. In “If My Death Could Be a Whale Fall” (2), “Imagine” (8), and “In the Line at Starbucks” (11), and in many more—though particularly these three poems—Stevenson Grellas addresses the importance not only of giving back but creating a sense of legacy. “If My Death Could Be a Whale Fall” imagines a world where the narrator’s body would sink like a whale to the lower throes of the ocean, creating an offering to the bottom feeders, while the narrator in “Imagine” pictures herself as an old woman, feeding the birds, and her memory and hope living on in their feathers (pun intended, thanks to Sylvia Plath). Finally, “In the Line at Starbucks” captures that sweet moment of our days simply made better by a covered cup of coffee and paying it forward to the next person in line. Though there is grief and loss in this collection, it’s a call, a bird song, a wind chime, and even whale song to look at life as a blessing, to see beauty in the daily things, and to be kinder to each other—and it’s a call we can all hear if we’re willing to listen.

With beautiful echoes of Sylvia Plath, Robert Creeley, Michael Burkard, Brigit Pegeen Kelly, and of course, Robert Bly, Handful of Stallions at Twilight gently and truthfully navigates heartache and loss but equally challenges the reader to go into the beyond where hope resides. No matter how much she might encourage us to look back over our shoulder, Carol Lynn Stevenson Grellas always eventually takes us to that place beyond.